In the January/ February 2022 issue of Smithsonian Magazine, there was a very interesting article by Jonny Diamond, editor-in-chief of LitHub.com, about old growth forests here in the Berkshires and Western Massachusetts and their advocate Bob Leverett. It has long been believed that old growth forests around here are gone, having been cut down in the 17th century to be used as fuel, fields to farm and timber with which to build.

But the loggers missed a few spots over the 300 years, such as areas in Ice Glen ravine in Stockbridge, Mohawk Trail State Forest in Charlemont, on Mount Greylock and other locations.

So, what exactly is an old growth forest? Well, according to the Smithsonian article, there is no universally accepted definition. The term came into use in the 1970’s to describe multi-species forests that have been left alone for at least 150 years. Ice Glen, so-named for the deposits of ice that lived in its deep, rocky crevasses well into the summer months, has such biota. Two-hundred-year old hemlocks and other inhabitants of northern-hardwood forests still exist there.

According to the article, beginning in the 1980’s while Bob and his son Rob were doing their weekend hikes, he started to notice in hard-to-reach spots, hidden patches of forest that evoked the primeval woods of his childhood, the ancient hemlocks and towering white pines of the Great Smoky Mountains near where he was born and raised. According to Bob, a lot of people, including forest ecologists, were skeptical, and he witnessed confusion among the experts about how to recognize and interpret old growth characteristics in the Berkshire forests.

Bob went public with his observations in the Spring of 1988 edition of the newsletter Woodland Steward, with an article about discovering old growth forest in the Deerfield River gorges of Massachusetts. Harvard researcher Tad Zebryk tagged along with him one day on a hike near the NY/MA border near Sheffield, MA. Zebryk brought along an increment borer (used for making estimates on the age of trees based upon its rings). After boring and examining, the age of one tree there came out to be 330 years old!

Leverett began taking meticulous measurements of the height and circumference of old trees and came up with another startling revelation: the heights of mature trees were commonly being mismeasured with the traditional tape and clinometer combination.

Using a surveyor’s transit, Bob and Jack Sobon, a specialist in timber-frame construction, would cross-triangulate the location of the top of a tree relative to its base, thereby significantly increasing accuracy. Measuring for height with the equipment of the day, no one apparently – not lumberjacks, foresters, or ecologists — typically allowed for the fact that the tops of most mature trees seldom stay vertically over their bases, invalidating the main premise of their measuring method. Bob, during the same period as ecologist Robert Van Pelt of University of Washington and big tree hunter Michael Taylor, developed a better way to accurately measure a tree’s height within inches. Named by Leverett as the Sine Method, it employs a laser rangefinder (introduced in the 1990s) and an angle measurer.

Bob also developed superior ways to measure trunk, limb and crown volume. The results have contributed to his discoveries about heightened carbon-capture abilities. A recent study Leverett co-authored with climate scientist William Moomaw and Susan Masino, a professor of applied science at Trinity College, found that individual Eastern white pines capture more carbon between 100 and 150 years of age than they do in their first 50 years. That study and others challenged the longstanding assumption that younger, faster growing forests sequester more carbon than mature forests. It bolsters the theory of “proforestation” as the simplest and most effective way to mitigate climate change through forests. “If we simply left the world’s existing forests alone, by 2100 they’d have captured enough carbon to offset years’ worth of global fossil-fuel emissions, up to 120 billion metric tons”.

Trees can keep adding a lot of carbon at much older ages than thought previously, particularly for New England’s white pine, hemlock and sugar maples. Bob Leverett literally wrote the book on how to measure a tree: American Forests Champion Trees Measuring Guidelines Handbook, co-authored with Don Bertolette, a veteran of the US Forest Service.

If the goal is to minimize global warning, cites Smithsonian, climate scientists often stress the importance of afforestation (planting new trees) and reforestation (regrowing forests). But according to climate scientist William Moomaw, there is a third approach to managing existing forests: proforestation (the preservation of older existing forests). He provided hard data that older trees accumulate far more carbon later in their life cycles than many had realized: they can accumulate 75% of their total carbon after 50 years of age.

Leverett’s work has made him a legend among “big tree hunters.” They meticulously measure and record data – the height of a hemlock, the trunk diameter of an elm, the crown spread of a white oak – for inclusion in the open database maintained by the Native Tree Society, co-founded by Leverett. To convince tree lovers and environmentalists, Bob started in the early 1990’s to write a series of articles for the quarterly journal Wild Earth to help spread his ideas about old growth. He has led thousands of people on tours of old-growth forests for groups like Mass Audubon, Sierra Club, ecologists, activists, builders, backpackers, painters, poets and others.

His work, along with that of Dr. Anthony D’Amato (now of University of Vermont), has helped to ensure the protection of 1,200 acres of old growth in the Commonwealth’s Forest Reserves. His message is “We have a duty to protect an old-growth forest, for both its beauty and its importance to the planet”.

“There’s a spiritual quality to being out here: You walk silently through these woods, and there’s a spirit that comes out. Other people are more eloquent in the way they describe the impact of the woodland on the human spirit. I just feel it”.

I think many an outdoor enthusiast will agree with Bob.

Knowing that habitat managers for MassWildlife are high on early successional growth, (which provides food for birds and other wildlife), I posed this question to DFW and DCR officials. Do you have old forest growth in your areas, and would you try to protect it? The DFW answer was, “We don’t think there are any on our Wildlife Management Areas, but if we did find some, we definitely would not cut them down or otherwise harm them. We have some large trees on our properties, but steer away from cutting them”.

DCR’s official response was that they manage approximately 500,000 acres of land across the Commonwealth, with a little more than a thousand acres of that land containing old growth forests. While there are many contributing factors the agency utilizes to define an old growth forest, in general these types of forests are typically several hundred years old.

In order for a forest to reach full maturity and attain old growth status, it needs to avoid significant disturbances, such as wildland fires, invasive tree pests, diseases, high-impact storms, and human-caused activities. Furthermore, most of the old growth forests in Massachusetts are located deep within parks, forests, and reservations, and are off trail. To help preserve these ancient forests, DCR refrains from publicizing their locations to better protect them and ensure they are less trafficked; however, most are located in the western part of the Commonwealth. Additionally, old growth forests are protected natural lands, and DCR’s policy is to preserve them, while also allowing the forest to self-manage.

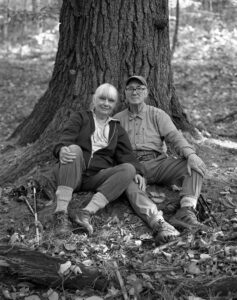

I contacted Bob to see if I could obtain a different picture of him that was not copyrighted by Smithsonian. He said yes, but I had to go through his photographer who has the copyright. He introduced me to David Degner online who he thought was in Germany. When I contacted David, he was actually in Tunisia and agreed to send a picture. He normally collects a fee for a picture but asked only if I would credit him for the picture and give his email address.

Thanks to David, Bob and all involved who helped with this article.

Actually, one could say that this was truly an international effort to bring you this picture.

Questions/comments: Berkwoodsandwaters@gmail.com. Phone: (413) 637-1818.